TESLA PATENTS

| SYSTEM OF TRANSMISSION OF ELECTRICAL ENERGY |

|

|

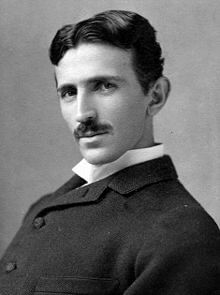

UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. NIKOLA TESLA OF NEW YORK, N. Y. SYSTEM OF TRANSMISSION OF ELECTRICAL ENERGY. SPECIFICATION forming part of Letters Patent No. 645,576, dated March 20, 1900. Application filed September 2, 1897. Serial No. 650,343. (No model.)To all whom it may concern: Be it known that I, NIKOLA TESLA, a citizen of the United States, residing at New York, in the county and State of New York, have invented certain new and useful improvements in Systems of Transmission of Electrical Energy, of which the following is a specification, reference being had to the drawing accompanying and forming a part of the same. It has been well known heretofore that by rarefying the air inclosed in a vessel its insulating properties are impaired to such an extent that it becomes what may be considered as a true conductor, although one of admittedly very high resistance. The practical information in this regard has been derived from observations necessarily limited in their scope by the character of the apparatus or means heretofore known and the quality of the electrical effects producible thereby. Thus it has been shown by William Crookes in his classical researches, which have so far served as the chief source of knowledge of this subject, that all gasses behave as excellent insulators until rarefied to a point corresponding to a barometric pressure of about seventy-five millimeters, and even at this very low pressure the discharge of a high-tension induction-coil passes through only a part of the attenuated gas in the form of a luminous thread or arc, a still further and considerable diminution of the pressure being required to render the entire mass of the gas inclosed in a vessel conducting. While this is true in every particular so long as electromotive or current impulses such as are obtainable with ordinary forms of apparatus are employed, I have found that neither the general behavior of the gases nor the known relations between electrical conductivity and barometric pressure are in conformity with these observations when impulses are used such as are producible by methods and apparatus described by me and which have peculiar and hitherto unobserved properties and are of effective electromotive force, measuring many hundred thousands or millions of volts. Through the continuous perfection of these methods and apparatus and the investigation of the actions of these current impulses I have been led to the discovery of certain highly-important useful facts which have hitherto been unknown. Among these and bearing directly upon the subject of my present application are the following: First, that atmospheric or other gases, even under normal pressure, when they are known to behave as perfect insulators, are in a large measure deprived of their dielectric properties by being subjected to the influence of electromotive impulses of the character and magnitude I have referred to and assume conducting and other qualities which have been so far observed only in gases greatly attenuated or heated to a high temperature, and, second, that the conductivity imparted to the air or gases increases very rapidly both with the augmentation of the applied electrical pressure and with the degree of rarefaction, the law in this latter respect being, however, quite different from that heretofore established. In illustration of these facts a few observations, which I have made with apparatus devised for the purposes here contemplated, may be cited. For example, a conductor or terminal, to which impulses such as those here considered are supplied, but which is otherwise insulated in space and is remote from any conducting-bodies, is surrounded by a luminous flame-like brush or discharge often covering many hundreds or even as much as several thousands of square feet of surface, this striking phenomenon clearly attesting the high degree of conductivity which the atmosphere attains under the influence of the immense electrical stresses to which it is subjected. This influence is however, not confined to that portion of the atmosphere which is discernible by the eye as luminous and which, as has been the case in some instances actually observed, may fill the space within a spherical or cylindrical envelop of a diameter of sixty feet or more, but reaches out to far remote regions, the insulating qualities of the air being, as I have ascertained, still sensibly impaired at a distance many hundred times that through which the luminous discharge projects from the terminal and in all probability much farther. The distance extends with the increase of the electromotive force of the impulses, with the diminution of the density of the atmosphere, with the elevation of the active terminal above the ground, and also, apparently, in slight measure, with the degree of moisture contained in the air. I have likewise observed that this region of decidedly-noticeable influence continuously enlarges as time goes on, and the discharge is allowed to pass not unlike a conflagration which slowly spreads, this being possibly due to the gradual electrification or ionization of the air or to the formation of less insulating gaseous compounds. It is, furthermore, a fact that such discharges of extreme tensions, approximating those of lightning, manifest a marked tendency to pass upward away from the ground, which may be due to electrostatic repulsion, or possibly to slight heating and consequent rising of the electrified or ionized air. These latter observations make it appear probable that a discharge of this character allowed to escape into the atmosphere from a terminal maintained at a great height will gradually leak through and establish a good conducting-path to more elevated and better conducting air strata, a process which possibly takes place in silent lightning discharges frequently witnessed on hot and sultry days. It will be apparent to what an extent the conductivity imparted to the air is enhanced by the increase of the electromotive force of the impulses when it is stated that in some instances the area covered by the flame discharge mentioned was enlarged more than sixfold by an augmentation of the electrical pressure, amounting scarcely to more than fifty per cent. As to the influence of rarefaction upon the electric conductivity imparted to the gases it is noteworthy that, whereas the atmospheric or other gases begin ordinarily to manifest this quality at something like seventy-five millimeters barometric pressure with the impulses of excessive electromotive force to which I have referred, the conductivity, as already pointed out, begins even at normal pressure and continuously increases with the degree of tenuity of the gas, so that at, say, one hundred and thirty millimeters pressure, when the gases are known to be still nearly perfect insulators for ordinary electromotive forces, they behave toward electromotive impulses of several millions of volts, like excellent conductors, as though they were rarefied to a much higher degree. By the discovery of these facts and the perfection of means for producing in a safe, economical, and thoroughly-practicable manner current impulses of the character described it becomes possible to transmit through easily-accessible and only moderately-rarefied strata of the atmosphere electrical energy not merely in insignificant quantities, such as are suitable for the operation of delicate instruments and like purposes, but also in quantities suitable for industrial uses on a large scale up to practically any amount and, according to all the experimental evidence I have obtained, to any terrestrial distance. To conduce to a better understanding or this method of transmission of energy and to distinguish it clearly, both in its theoretical aspect and in its practical bearing; from other known modes of transmission, it is useful to state that all previous efforts made by myself and others for transmitting electrical energy to a distance without the use of metallic conductors, chiefly with the object of actuating sensitive receivers, have been based, in so far as the atmosphere is concerned, upon those qualities which it possesses by virtue of its being an excellent insulator, and all these attempts would have been obviously recognized as ineffective if not entirely futile in the presence of a conducting atmosphere or medium. The utilization of any conducting properties of the air for purposes of transmission of energy has been hitherto out of the question in the absence of apparatus suitable for meeting the many and difficult requirements, although it has long been known or surmised that atmospheric strata at great altitudes—say fifteen or more miles above sea-level—are, or should be, in a measure, conducting; but assuming even that the indispensable means should have been produced then still a difficulty, which in the present state of the mechanical arts must be considered as insuperable, would remain—namely, that of maintaining terminals at elevations of fifteen miles or more above the level of the sea. Through my discoveries before mentioned and the production of adequate means the necessity of maintaining terminals at such inaccessible altitudes is obviated and a practical method and system of transmission of energy through the natural media is afforded essentially different from all those available up to the present time and possessing, moreover, this important practical advantage, that whereas in all such methods or systems heretofore used or proposed but a minute fraction of the total energy expended by the generator or transmitter was recoverable in a distant receiving apparatus by my method and appliances it is possible to utilize by far the greater portion of the energy of the source and in any locality however remote from the same. Expressed briefly, my present invention, based upon these discoveries, consists then in producing at one point an electrical pressure of such character and magnitude as to cause thereby a current to traverse elevated strata of the air between the point of generation and a distant point to which the energy is to be received and utilized. In the accompanying drawing a general arrangement of apparatus is diagrammatically illustrated such as I contemplate employing in the carrying out of my invention on an industrial scale—as, for instance, for lighting distant cities or districts from places where cheap power is obtainable. Referring to the drawing, A is a coil, generally of many turns and of a very large diameter, wound in spiral form either about a magnetic core or not, as may be found necessary, C is a second coil, formed of a conductor of much larger section and smaller . . . . . . . . . even thousands of miles, with terminals not more than thirty to thirty-five thousand feet above the level of the sea, and even this comparatively-small elevation will be required chiefly for reasons of economy, and, if desired, it may be considerably reduced, since by such means as have been described practically any potential that is desired may be obtained, the currents through the air strata may be rendered very small, whereby the loss in the transmission may be reduced. It will be understood that the transmitting as well as the receiving coils, transformers, or other apparatus may be in some cases moveable–as, for example, when they are carried by vessels floating in the air or by ships at sea. In such a case, or generally, the connection of one of the terminals of the high-tension coil or coils to the ground may not be permanent, but may be intermittently or inductively established, and any such or similar modifications I shall consider as within the scope of my invention. While the description here given contemplates chiefly a method and system of energy transmission to a distance through the natural media for industrial purposes, the principles which I have herein disclosed and the apparatus which I have shown will obviously have many other valuable uses–as, for instance, when it is desirable to transmit intelligible messages to great distances, or to illuminate upper strata of the air, or to produce, designedly, any useful changes in the condition of the atmosphere, or to manufacture from the gases of the same products, as nitric acid, fertilizing compounds, or the like, by the action of such current impulses, for all of which and for many other valuable purposes they are eminently suitable, and I do not wish to limit myself in this respect. Obviously, also, certain features of my invention here disclosed will be useful as disconnected from the method itself–as, for example, in other systems of energy transmission, for whatever purpose they may be intended, the transmitting and receiving transformers arranged and connected as illustrated, the feature of a transmitting and receiving coil or conductor, both connected to the ground and to an elevated-terminal and adjusted so as to vibrate in synchronism, the proportioning of such conductors or coils, as above specified, the feature of a receiving-transformer, with its primary connected to earth and to an elevated terminal and having the operative devices in its secondary, and other features or particulars, such as have been described in this specification or will readily suggest themselves by a perusal of the same. I do not claim in this application a transformer for developing or converting currents of high potential in the form herewith shown and described and with the two coils connected together, as and for the purpose set forth, having made these improvements the subject of a p:\tent granted to me November 2, 1897, No. 593,138, nor do I claim herein the apparatus employed in carrying out the method of this application when such apparatus is specially constructed find arranged for securing the particular object sought in the present invention, as these last-named features are made the subject of an application filed as a division of this application on February 19,1900, Serial No. 5,780. What I now claim is– 1. The method hereinbefore described of transmitting electrical energy through the natural media, which consists in producing at a generating-station a very high electrical pressure, causing thereby a propagation or flow of electrical energy; by conduction, through the earth and the air strata, and collecting or receiving at a. distant point the electrical energy so propagated or caused to flow. 2. The method hereinbefore described of transmitting electrical energy, which consists in producing at a generating-station a very high electrical pressure, conducting the cur- S rent caused thereby to earth and to a terminal at an elevation at which the atmosphere serves as a conductor therefor and collecting the current by a second elevated terminal at a distance from the first. 3. The method hereinbefore described of transmitting electrical energy through the natural media, which consists in producing between the earth and a generator-terminal elevated above the same, at a generating-station, a sufficiently-high electromotive force to render elevated air strata conducting, causing thereby a propagation or flow of electrical energy, by conduction, through the air strata, and collecting or receiving at a point distant from the generating-station the electrical energy so propagated or caused to flow. 4. The method hereinbefore described of transmitting electrical energy through the natural media, which consists in producing between the earth and a generator-terminal elevated above the same, at a generating-station, a sufficiently-high electromotive force to render the air strata at or near the elevated terminal conducting, causing thereby a propagation or flow of electrical energy, by conduction, through the air strata, and collecting or receiving at a point distant from the generating-station the electrical energy so propagated or caused to flow. 5. The method hereinbefore described of transmitting electrical energy through the natural media, which consists in producing between the earth and a generator-terminal elevated above the same, at a generating-station, electrical impulses of a sufficiently-high electromotive force to render elevated air strata conducting, causing thereby current impulses to pass, by conduction, through the air strata, and collecting or receiving at a point distant from the generating-station, the energy of the current impulses by means of a circuit synchronized with the impulses. 6. The method hereinbefore described of . . . . . . 9. The method hereinbefore described of transmitting electrical energy through the natural media, which consists in generating current impulses of relatively-low electromotive force at a generating-station, utilizing such impulses to energize the primary of a transformer, generating by means of such primary circuit impulses in a secondary surrounding by the primary and connected to the earth and to an elevated terminal, of sufficiently-high electromotive force to render elevated air strata conducting, causing thereby impulses to be propagated through the air strata, collecting or receiving the energy of such impulses, at a point distant from the generating-station, by means of a receiving circuit connected to the earth and to an elevated terminal, and utilizing the energy so received to energize a secondary circuit of low potential surrounding the receiving-circuit. NIKOLA TESLA Witnesses: M. Lawson Dyer, G. W. Martling. |

| ELECTRICAL TRANSFORMER Transformer for High-Frequency Lighting |

|

|

||

|

UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. NIKOLA TESLA OF NEW YORK, N. Y. Electrical Transformer. SPECIFICATION forming part of Letters Patent No. 593,138, dated November 2, 1897. Application filed March 20, 1897. Serial No. 629,453. (No model.)To all whom, it may concern: Be it known that I, NIKOLA TESLA, a citizen of the United States, residing at New York, in the county and State of New York, have invented certain new and useful Improvements in Electrical Transformers, of which the following is a specification, reference being had to the drawings accompanying and forming a part of the same. The present application is based upon an apparatus which I have devised and employed for to purpose of developing electrical currents of high potential, which transformers or induction-coils constructed on the principles heretofore followed in the manufacture of such instruments are wholly incapable of producing or practically utilizing, at least without serious liability of the destruction of the apparatus itself and danger to persons approaching or handling it. The improvement involves a novel form of transformer or induction-coil and a system for the transmission of electrical energy by means of the same in which the energy of the source is raised to a much higher potential for transmission over the line than has ever been practically employed heretofore, and the apparatus is constructed with reference to the production of such a potential and so as to be not only free from the danger of injury from the destruction of insulation, but safe to handle. To this end I construct an induction-coil or transformer in which the primary and secondary coils are wound or arranged in such manner that the convolutions of the conductor of the latter will be farther removed from the primary as the liability of injury from the effects of potential increases, the terminal or point of highest potential being the most remote, and so that between adjacent convolutions there shall be the least possible difference of potential. The type of coil in which the last-named features are present is the flat spiral, and this form I generally employ, winding the primary on the outside of the secondary and taking off the current from the latter at the center or inner end of the spiral. I may depart from or vary this form, however, in the particulars hereinafter specified. In constructing my improved transformers I employ a length of secondary which is approximately one-quarter of the wave length of the electrical disturbance in the circuit including the secondary coil, based on the velocity of propagation of electrical disturbances through such circuit, or, in general, of such length that the potential at the terminal of the secondary which is the more remote from the primary shall be at its maximum. In using these coils I connect one end of the secondary, or that in proximity to the primary, to earth, and in order to more effectively provide against injury to persons or to the apparatus I also connect it with the primary. In the accompanying drawings, Figure 1 is a diagram illustrating the plan of winding and connection which I employ in constructing my improved coils and the manner of using them for the transmission of energy over long distances. Fig. 2 is a side elevation, and Fig. 3 a side elevation and part section, of modified forms of induction-coil made in accordance with my invention. A designates a core, which may be magnetic when so desired. B is the secondary coil, wound upon said core in generally spiral form. C is the primary, which is wound around in proximity to the secondary. One terminal of the latter will be at the center of the spiral coil, and from this the current is taken to line or for other purposes. The other terminal of the secondary is connected to earth and preferably also to the primary. When two coils are used in a transmission system in which the currents are raised to a high potential and then reconverted to a lower potential, the receiving-transformer will be constructed and connected in the same manner as the first-that is to say, the inner or center end of what corresponds to the secondary of the first will be connected to line and the other end to earth and to the local circuit or that which corresponds to the primary of the first. In such case also the line-wire should be supported in such manner as to avoid loss by the current jumping from line to objects in its vicinity and in contact with earth–as, for example, by means of long insulators, mounted, preferably, on metal poles so that in case of leakage from the line it will pass harmlessly to earth. In Fig. 1 where such a system is illustrated, a dynamo G is conveniently represented as supplying the primary of the sending or “step-up” transformer, and lamps II and motors K are shown as connected with the corresponding circuit of the receiving or “step-down” transformer. Instead of winding the coils in the form of a flat spiral the secondary may be wound on a support in the shape of a frustum of a cone and the primary wound around its base, as shown in Fig. 2. In practice for apparatus designed for ordinary usage the coil is preferably constructed on the plan illustrated in Fig. 3. In this figure L L are spools of insulating material upon which the secondary is wound-in the present case, however, in two sections, so as to constitute really two secondaries. The primary C is a spirally-wound flat strip surrounding both secondaries B. The inner terminals of the secondaries are led out through tubes of insulating material M, while the other or outside terminals are connected with the primary. The length of the secondary coil B or of each secondary coil when two are used, as in Fig. 3, is, as before stated, approximately one-quarter of the wave length of the electrical disturbance in the secondary circuit, based on the velocity of propagation of the electrical disturbance through the coil itself and the circuit with which it is designed to be used-that is to say, if the rate at which a current traverses the circuit, including the coil, be one hundred and eighty-five thousand miles per second, then a frequency of nine hundred and twenty-five per second would maintain nine hundred and twenty-five stationary waves in a circuit one hundred and eighty-five thousand miles long, and each wave length would be two hundred miles in length. For such a frequency I should use a secondary fifty miles in length, so that at one terminal the potential would be zero and at the other maximum. Coils of the character herein described have several important advantages. As the potential increases with the number of turns the difference of potential between adjacent turns is comparatively small, and hence a very high potential, impracticable with ordinary coils, may be successfully maintained. As the secondary is electrically connected with the primary the latter will be at substantially the same potential as the adjacent portions of the secondary, so that there will be no tendency for sparks to jump from one to the other and destroy the insulation. Moreover, as both primary and secondary are grounded and the line-terminal of the coil carried and protected to a point remote from the apparatus the danger of a discharge through the body of a person handling or approaching the apparatus is reduced to a minimum.I am aware that an induction-coil in the form of a flat spiral is not in itself new, and this I do not claim; but What I claim as my invention is—1. A transformer for developing or converting currents of high potential, comprising a primary and secondary coil, one terminal of the secondary being electrically connected with the primary; and with earth when the transformer is in use, as set forth. 2. A transformer for developing or converting currents of high potential, comprising a primary and secondary wound in the form of a flat spiral, the end of the secondary adjacent to the primary being electrically connected therewith and with earth when the transformer is in use, as set forth. 3. A transformer for developing or converting currents of high potential comprising a primary and secondary wound in the form of a spiral, the secondary being inside of, and surrounded by, the convolutions of the primary and having its adjacent terminal electrically connected therewith and with earth when the transformer is in use, as set forth. 4. In a system for the conversion and transmission of electrical energy, the combination of two transformers, one for raising, the other for lowering, the potential of the currents, the said transformers having one terminal of the longer or fine-wire coils connected to line, and the other terminals adjacent to the shorter coils electrically connected therewith and to the earth, as set forth. NIKOLA TESLA. Witnesses: M. LAWSON DYER, G. W. MARTLING. |

| COIL FOR ELECTROMAGNETS |

|

|

| UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICENIKOLA TESLA, OF NEW YORK, N. Y. COIL FOR ELECTRO-MAGNETS.

SPECIFICATION forming part of Letters Patent No. 512,340, dated January 9, 1894. Application filed July 7, 1893. Serial No. 479,804. (No model.) To all whom it may concern: Be it known that I, NIKOLA TESLA, a citizen of the United States, residing at New York, in the county and State of New York, have invented certain new and useful improvements in Coils for Electro-Magnets and other apparatus, of which the following is a specification, reference being had to the drawings accompanying and forming a part of the same. In electric apparatus or systems in, which alternating currents are employed the self-induction of the coils or conductors may, and, in fact, in many cases does operate disadvantageously by giving rise to false currents which often reduce what is known as the commercial efficiency of the apparatus composing the system or operate detrimentally in other respects. The effects of self-induction, above referred to, are known to be neutralized by proportioning to a proper degree the capacity of the circuit with relation to the self-induction and frequency of the currents. This has been accomplished heretofore by the use of condensers constructed and applied as separate instruments. My present invention has for its object to avoid the employment of condensers, which are expensive, cumbersome and difficult to maintain in perfect condition, and to so construct the coils themselves as to accomplish the same ultimate object. I would here state that by the term coils I desire to include generally helices, solenoids, or, in fact, any conductor the different parts of which by the requirements of its application or use are brought into such relations with each other as to materially increase the self-induction. I have found that in every coil there exists a certain relation between its self-induction and capacity that permits, a current of given frequency and potential to pass through it with no other opposition than that of ohmic resistance, or, in other words, as though it possessed no self-induction. This is due to the mutual relations existing between the special character of the current and the self-induction and capacity of the coil, the latter quantity being just capable of neutralizing the self-induction for that frequency. It is well known that the higher the frequency or potential difference of the current the smaller the capacity required to counteract the self-induction; hence, in any coil, however small the capacity, it may be sufficient for the purpose stated if the proper conditions in other respects be secured in the ordinary coils the difference of potential between adjacent turns or spirals is very small, so that while they are in a sense condensers, they possess but very small capacity and the relations between the two quantities, self-induction and capacity, are not such as under any ordinary conditions satisfy the requirements herein contemplated, because the capacity relatively to the self-induction is very small. In order to attain my object and to properly increase the capacity of any given coil, I wind it in such way as to secure a greater difference of potential between its adjacent turns or convolutions, and since the energy stored in the coil-considering the latter as a condenser, is proportionate to the square of the potential difference between its adjacent convolutions, it is evident that I may in this way secure by the proper disposition of these convolutions I greatly increased capacity for a given increase in potential difference between the turns. I have illustrated diagrammatically in the accompanying drawings the general nature of the plan which I adopt for carrying out this invention. Figure 1 is a diagram of a coil wound in the ordinary manner. Fig. 2 is a diagram of a winding designed to secure the objects of my invention. Let Fig. 1, designate any given coil the spires or convolutions of which are wound upon and insulated from each other. Let it be assumed that the terminals of this coil show a potential difference of one hundred volts, and that there are one thousand convolutions: then considering any two contiguous points on adjacent convolutions let it be assumed that there will exist between them a potential difference of one-tenth of a volt. If now, as shown in Fig. 2, a conductor B be wound parallel with the conductor A and insulated from it, and the end of A be connected with the starting point of B, the aggregate length of the two conductor being such that the assumed number of convolutions or turns is the same, vis, one thousand, then the potential difference between any to adjacent points in A and B will be fifty volts, and as the capacity effect is proportionate to the square of this difference, the energy stored in the coil as a whole will now be two hundred and fifty thousand as great. Following out this principle, I may wind any given coil either in whole or in part, not only in the specific manner herein illustrated, but in a great variety of ways, well known in the art, so as to secure between adjacent convolutions such potential difference as will give the proper capacity to neutralize the self-induction for any given current that may be employed. Capacity secured in this particular way possesses an additional advantage in that it is evenly distributed, a consideration of the greatest importance in many cases, and the results, both as to efficiency and economy, are the more readily and easily obtained as the size of the coils, the potential difference or frequency of the currents are increased. Coils composed of independent strands or conductors wound side by side and connected in series are not In themselves new, and I do not regard a more detailed description of the same necessary. But heretofore, so far as I am aware, the objects in view have been essentially different from mine, and the results which I obtain even if an incident to such forms of winding have not been appreciated or taken advantage of. In carrying out my invention it is to be observed that certain facts are well understood by those skilled in the art, viz: the relations of capacity, self-induction, and the frequency and potential difference of the current. What capacity, therefore, in any given case it is desirable to obtain and what special winding will secure it, are readily determinable from the other factors which are known. What I claim as my invention is— 1. A coil for electric apparatus the adjacent convolutions of which form parts of the circuit between which there exists a potential difference sufficient to secure in the coil a capacity capable of neutralizing its self-induction, as hereinbefore described. 2. A coil composed of contiguous or adjacent insulated conductors electrically connected in series and having a potential difference of such value as to give to the coil as a whole, a capacity sufficient to neutralize its self-induction, as set forth.

Witnesses: ROBT. F. GAYLORD, PARKER W. PAGE. |

| MEANS FOR INCREASING THE INTENSITY OF ELECTRICAL OSCILLATIONS |

|

|

|

UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. NIKOLA TESLA, OF NEW YORK, N. Y. MEANS FOR INCREASING THE INTENSITY OF ELECTRICAL OSCILLATIONS. SPECIFICATION forming part of Letters Patent No. 685,012, dated October 23, 1901. Application filed March 21, 1900, Renewed July 3, 1901, Serial No. 66,980 (No Model.) To all whom it may concern: Be it known that I, NIKOLA TESLA, a citizen of the United States, residing at the borough of Manhattan, in the city, county, and State of New York, have invented certain new and useful Improvements in Means for Increasing the Intensity of Electrical Oscillations, of which the following is a specification, reference being had to the drawings accompanying and forming part of the same. In many scientific and practical uses of electrical impulses or oscillations預s, for example, in systems of transmitting intelligence to distant points擁t is of great importance to intensify as much as possible the current impulses or vibrations which are produced in the circuits of the transmitting and receiving instruments, particularly of the latter. It is well known that when electrical impulses are impressed upon a circuit adapted to oscillate freely the intensity of the oscillations developed in the same is dependent on the magnitude of its physical constants and the relation of the periods of the impressed and of the free oscillations. For the attainment of the best result it is necessary that the periods of the impressed should be the same as that of the free oscillations, under which conditions the intensity of the latter is greatest and chiefly dependent on the inductance and resistance of the circuit, being directly proportionate to the former and inversely to the latter. In order, therefore, to intensify the impulses or oscillations excited in the circuit擁n other words, to produce the greatest rise of current or electrical pressure in the same擁t is desirable to make its inductance as large and its resistance as small as practicable. Having this end in view I have devised and used conductors of special forms and of relatively very large cross-section; but I have found that limitations exist in regard to the increase of the inductance as well as to the diminution of the resistance. This will be understood when it is borne in mind that the resonant rise of current or pressure in a freely-oscillating circuit is proportionate to the frequency of the impulses and that a large inductance in general involves a slow vibration. On the other hand, an increase of the section of the conductor with the object of reducing its resistance is, beyond a certain limit, of little or no value, principally because electrical oscillations, particularly those of high frequency, pass mainly through the superficial conducting layers, and while it is true that this drawback may be overcome in a measure by the employment of thin ribbons, tubes, or stranded cables, yet in practice other disadvantages arise, which often more than offset the gain. It is a well-established fact that as the temperature of a metallic conductor rises its electrical resistance increases, and in recognition of this constructors of commercial electrical apparatus have heretofore resorted to many expedients for preventing the coils and other parts of the same from becoming heated when in use, but merely with a view to economizing energy and reducing the cost of construction and operation of the apparatus. Now I have discovered that when a circuit adapted to vibrate freely is maintained at a low temperature the oscillations excited in the same are to an extraordinary degree magnified and prolonged, and I am thus enabled to produce many valuable results which have heretofore been wholly impracticable. Briefly stated, then, my invention consists in producing a great increase in the intensity and duration of the oscillations excited in a freely-vibrating or resonating circuit by maintaining the same at a low temperature. Ordinarily in commercial apparatus such provision is made only with the object of preventing wasteful heating, and in any event its influence upon the intensity of the oscillations is very slight and practically negligible, for as a rule impulses of arbitrary frequency are impressed upon a circuit, irrespective of its own free vibrations, and a resonant rise is expressly avoided. My invention, it will be understood, does not primarily contemplate the saving of energy, but aims at the attainment of a distinctly novel and valuable result葉hat is, the increase to the greatest practicable degree of the intensity and duration of free oscillations. It may be usefully applied in all cases when this special object is sought, but offers exceptional advantages in those instances in which the freely-oscillating discharges of a condenser, are utilized. The best and most convenient manner of carrying out the invention of which I am now aware is to surround the freely-vibrating circuit or conductor, which is to be maintained at a low temperature, with a suitable cooling medium, which may be any kind of freezing mixture or agent, such as liquid air, and in order to derive the fullest benefit from the improvement the circuit should be primarily constructed so as to have the greatest possible self-induction and the smallest practicable resistance, and other rules of construction which are now recognized should be observed. For example, when in a system of transmission of energy for any purpose through the natural media the transmitting and receiving conductors are connected to earth and to an insulated terminal, respectively, the lengths of these conductors should be one-quarter of the wave length of the disturbance propagated through them. In the accompanying drawing I have shown graphically a disposition of apparatus which may be used in applying practically my invention. The drawing illustrates in perspective two devices, either of which may be the transmitter, while the other is the receiver. In each there is a coil of few turns and low resistance, (designated in one by A and in the other by A’.) The former coil, supposed to be forming part of the transmitter, is to be connected with a suitable source of current, while the latter is to be included in circuit with a receiving device. In inductive relation to said coils in each instrument is a flat spirally-wound coil B or B’, one terminal of which is shown as connected to a ground-plate C, while the other, leading from the center, is adapted to be connected to an insulated terminal, which is generally maintained at an elevation in the air. The coils B B’ are placed in insulating- receptacles D, which contain the freezing agent and around which the coils A and A’ are wound. Coils in the form of a flat spiral, such as those described, are eminently suited for the production of free oscillations; but obviously conductors or circuits of any other form may be used, if desired. From the foregoing the operation of the apparatus will now be readily understood. Assume, first, as the simplest case that upon the coil A of the transmitter impulses or oscillations of an arbitrary frequency and irrespective of its own free vibrations are impressed. Corresponding oscillations will then be induced in the circuit B, which, being constructed and adjusted, as before indicated, so as to vibrate at the same rate, will greatly magnify them, the increase being directly proportionate to the product of the frequency of the oscillations and the inductance of circuit B and inversely to the resistance of the latter. Other conditions remaining the same, the intensity of the oscillations in the resonating-circuit B will be increased in the same proportion as its resistance is reduced. Very often, however, the conditions may be such that the gain sought is not realized directly by diminishing the resistance of the circuit. In such cases the skilled expert who applies the invention will turn to advantage the reduction of resistance by using a correspondingly longer conductor, thus securing a much greater self-induction, and under all circumstances he will determine the dimensions of the circuit, so as to get the greatest value of the ratio of its inductance to its resistance, which determines the intensity of the free oscillations. The vibrations of coil B greatly strengthened, spread to a distance and on reaching the tuned receiving-conductor B’ excite corresponding oscillations in the same, which for similar reasons are intensified, with the result of inducing correspondingly stronger currents or oscillations in circuit A’, including the receiving device. When, as may be the case in the transmission of intelligible signals, the circuit A is periodically closed and opened, the effect upon the receiver is heightened in the manner above described not only because the impulses in the coils B and B’ are strengthened, but also on account of their persistence through a longer interval of time. The advantages offered by the invention are still more fully realized when the circuit A of the transmitter instead of having impulses of an arbitrary frequency impressed upon it is itself permitted to vibrate at its own rate, and more particularly so if it be energized by the freely-oscillating high-frequency discharges of a condenser. In such a case the cooling of the conductor A, which may be effected in any suitable manner, results in an extraordinary magnification of the oscillation in the resonating-circuit B, which I attribute to the increased intensity as well as greater number of the high-frequency oscillations obtained in the circuit A. The receiving coil B’ is energized stronger in proportion and induces currents of greater intensity in the circuits A’. It is evident from the above that the greater the number of the freely-vibrating circuits which alternately receive and transmit energy from one to another the greater, relatively, will be the gain secured by applying my invention. I do not-of course intend to limit myself to the specific manner and means described of artificial cooling, nor to the particular forms and arrangements of the circuits shown. By taking advantage of the facts above pointed out and of the means described I have found it possible to secure a rise of electrical pressure in an excited circuit very many times greater than has heretofore been obtainable, and this result makes it practicable, among other things, to greatly extend the distance of transmission of signals and to exclude much more effectively interference with the same than has been possible heretofore. Having now described my invention, what I claim is- 1. The combination with a circuit adapted to vibrate freely, of means for artificially cooling the same to a low temperature, as herein set forth. 2. In an apparatus for transmitting or receiving electrical impulses or oscillations, the combination with a primary and a secondary circuit, adapted to vibrate freely in response to the impressed oscillations, of means for artificially cooling the same to a low temperature, as herein set forth. 3. In a system for the transmission of electrical energy, a circuit upon which electrical oscillations are impressed, and which is adapted to vibrate freely, in combination with a receptacle containing an artificial refrigerant in which said circuit is immersed, as herein set forth. 4. The means of increasing the intensity of the electrical impulses or oscillations impressed upon a freely-vibrating circuit, consisting of an artificial refrigerant combined with and applied to such circuit and adapted to maintain the same at a low temperature. 5. The means of intensifying and prolonging the electrical oscillations produced in a freely-vibrating circuit, consisting of an artificial refrigerant applied to such circuit and adapted to maintain the same at a uniform low temperature. 6. In a system for the transmission of energy, a series of transmitting and receiving circuits adapted to vibrate freely, in combination with means for artificially maintaining the same at a low temperature, as set forth. NIKOLA TESLA. Witnesses: John C. Kerr, M. Lawson Dyer. |

| APPARATUS FOR TRANSMITTING ELECTRICAL ENERGY |

|

|

|

UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. NIKOLA TESLA, OF NEW YORK, N. Y. APPARATUS FOR TRANSMITTING ELECTRICAL ENERGY 1,119,732. Specification of Letters Patent. Patented Dec. 1, 1914.Application filed January 18. 1902, Serial No. 90,245. Renewed May 4, 1907. Serial No. 371,817. To all whom it may concern: Be it known that I, NIKOLA TESLA, a citizen of the United States, residing at the borough of Manhattan, in the city, county, and State of New York, have invented certain new and useful Improvements in Apparatus for Transmitting Electrical Energy, of which the following is a specification, reference being had to the drawing accompanying and forming a part of the same. In endeavoring to adapt currents or discharges of very high tension to various valuable uses, as the distribution of energy through wires from central plants to distant places of consumption, or the transmission of powerful disturbances to great distances, through the natural or non-artificial media. I have encountered difficulties in confining considerable amounts of electricity to the conductors and preventing its leakage over their supports, or its escape into the ambient air, which always takes place when the electric surface density reaches a certain value. The intensity of the effect of a transmitting circuit with a free or elevated terminal is proportionate to the quantity of electricity displaced which is determined by the product of the capacity of the circuit, the pressure, and the frequency of the currents employed. To produce an electrical movement of the required magnitude it is desirable to charge the terminal as highly as possible, for while a great quantity of electricity may also be displaced by a large capacity charged to low pressure, there are disadvantages met with in many cases when the former is made too large. These are due to the fact that, an increase of the capacity entails a lowering of the frequency of the impulses or discharges and a diminution of the energy of vibration. This will be understood when it is borne in mind, that a circuit with a large capacity behaves us a slackspring, whereas one with a small capacity acts a stiff spring, vibrating more vigorously. Therefore, in order to attain the highest possible frequency, which for certain purposes is advantageous and, apart from that, to develop the greatest energy in such a transmitting circuit, I employ a terminal of relatively small capacity, which I charge to as high a pressure as practicable. To accomplish this result I have found it imperative to so construct the elevated conductor, that its outer surface, on which the electrical charge chiefly accumulates, has itself a large radius of curvature, or is composed of separate elements which, irrespective of their own radius of curvature, are arranged in close proximity to each so other and so, that the outside ideal surface enveloping them is of a large radius. Evidently, the smaller the radius of curvature the greater, for a given electric displacement, will be the surface-density and, consequently the lower the limiting pressure to which the terminal may he charged without electricity escaping into the air. Such a terminal secure to an insulating support entering more or less into its interior, and I likewise connect the circuit to it inside or, generally, at points where the electric density is small. This plan of constructing and supporting a highly charged conductor I have found to be of great practical importance, and it may be usefully applied in many ways. Referring to the accompanying drawing, the figure is a view in elevation and part section of an improved free terminal and circuit of large surface with supporting structure and generating apparatus. The terminal D consists of a suitably shaped metallic frame, in this case a ring of nearly circular cross section, which is covered with half spherical metal plates P P, thus constituting a very large conducting surface, smooth on all places where the electric charge principally accumulates. The frame is carried by a strong platform expressly provided for safety appliances, instruments of observation, etc., which in turn rests on insulating supports F F. These should penetrate far into the hollow space formed by the terminal, and if the electric density at the points where they are bolted to the frame is still considerable, they may specially protected by conducting hoods as H. A part of the improvements which form the subject of this specification, the transmitting circuit, in its general features, is identical with that described and claimed in my original Patents Nos. 645,576 and 649,621. The circuit comprises a coil A which is in close inductive relation with a primary C, and one end of which is connected to a ground-plate E, while its other end is led through a separate self-induction coil B and a metallic cylinder B’ to the terminal D. The connection to the latter should always be made at, or near the center, in order to secure a symmetrical distribution of the current, as otherwise, when the frequency is very high and the flow of large volume, the performance of the apparatus might be impaired. The primary C may be excited in any desired manner, from a suitable source of currents G, which may be an alternator or condenser, the important requirement being that the resonant condition is established, that is to say, that the terminal D is charged to the maximum pressure developed in the circuit, as I have specified in my original patents before referred to. The adjustments should be made with particular care when the transmitter is one of great power, not only on account of economy, but also in order to avoid danger. I have shown to that it is practicable to produce in a resonating circuit as E A B B’ D immense electrical activities, measured by tens and even hundreds of thousands of horse-power, and in such a case, if the points of maximum pressure should be shifted below the terminal D, along coil B, a ball of fire might break out and destroy the support F or anything else in the way. For the better appreciation of the nature of this danger it should he stated, that the destructive action may take place with inconceivable violence. This will cease to be surprising when it is borne in mind, that the entire energy accumulated in the excited circuit, instead of requiring, as under normal working conditions, one quarter of the period or more for its transformation from static to kinetic form, may spend itself in an incomparably smaller interval of time, at a rate of many millions of horse power. The accident is apt to occur when, the transmitting circuit being strongly excited, the impressed oscillations upon it are caused, in any manner more or less sudden, to be more rapid than the free oscillations. It is therefore advisable to begin the adjustments with feeble and somewhat slower impressed oscillations. strengthening and quickening them gradually, until the apparatus has been brought under perfect control. To increase the safety, I provide on a convenient place, preferably on terminal D, one or more elements or plates either of somewhat smaller radius of curvature or protruding more or less beyond the others (in which case they maybe of larger radius of curvature) so that, should the pressure rise to a value, beyond which it is not desired to go, the powerful discharge may dart out there and lose itself harmlessly in air. Such a plate, performing a function similar to that of a safety valve on a high pressure reservoir, is indicated at V. Still further extending the principles underlying my invention, special reference is made to coil B and conductor B’. The latter is in the form of a cylinder with smooth or polished surface of a radius much larger than that of the half spherical elements P P, and widens out at the bottom into a hood H, which should be slotted to avoid loss by eddy currents and the purpose of which will be clear from the foregoing. The coil B is wound on a frame or drum D1 of insulating material, with its turns close together. I have discovered that when so wound the effect of the small radius of curvature of the wire itself is overcome and the coil behaves as a conductor of large radius of curvature, corresponding to that of the drum. This feature is of considerable practical importance and is applicable not only in this special instance, but generally. For example, such plates at P P of terminal D, though preferably of large radius of curvature, need not be necessarily so for provided only that the individual plates or elements of a high potential conductor or terminal are arranged in proximity to each other and with their outer boundaries along an ideal symmetrical enveloping surface of a large radius of curvature, the advantages of the invention will be more or less fully realized. The lower end of the coil B—which, if desired, may be extended up to the terminal D should be somewhat below the uppermost turn of coil A. This, I find, lessens the tendency of the charge to break out from the wire connecting both and to pass along the support F’. Having described my invention, I claim: 1. As a means for producing great electrical activities a resonant circuit having its outer conducting boundaries, which are charged to a high potential, arranged in surfaces of large radii of curvature so as to prevent leakage of the oscillating charge, substantially as set forth. 2. In apparatus for the transmission of electrical energy a circuit connected to ground and to an elevated terminal and having its outer conducting boundaries, which are subject to high tension, arranged in surfaces of large radii of curvature substantially as, and for the purpose described. 3. In a plant for the transmission of electrical energy without wires, in combination with a primary or exciting circuit a secondary connected to ground and to an elevated terminal and having its outer conducting boundaries, which are charged to a high potential, arranged in surfaces of large radii of curvature for the purpose of preventing leakage and loss of energy, substantially as set forth. 4. As a means for transmitting electrical energy to a distance through the natural media a grounded resonant circuit, comprising, a part upon which oscillations are impressed and another for raising the tension, having its outer conducting boundaries on which a high-tension charge accumulates arranged in surfaces of large radii of curvature, substantially as described. 5. The means for producing excessive electric potentials consisting of a primary exciting circuit and a resonant secondary having its outer conducting elements which are subject to high tension arranged in proximity to each other and in surface of large of curvature so as to prevent leakage of the charge and attendant lowering of potential, substantially as described. 6. A circuit comprising a part upon which oscillations are impressed and another part for raising the tension by resonance, the latter part being supported on places of low electric density and having its outermost conducting boundaries arranged in surfaces of large radii of curvature, as set forth. 7. In apparatus for the transmission of electrical energy without wires a grounded circuit the outer conducting elements of which have a great aggregate area and are arranged in surfaces of large radii of curvature so as to permit the storing of a high charge at a small electric density and prevent loss through leakage, substantially as described. 8. A wireless transmitter comprising in combination a source of oscillations as a condenser, a primary exciting circuit and a secondary grounded and elevated conductor the outer conducting boundaries of which are in proximity to each other and arranged in surfaces of large radii of curvature, substantially as described. 9. In apparatus for the transmission of electrical energy without wires an elevated conductor or antenna having its outer high potential conducting or capacity elements arranged in proximity to each other and in surfaces of large radii of curvature so as to overcome the effect of the small radius of curvature of the individual elements and leakage of the charge, as set forth. 10. A grounded resonant transmitting circuit having its outer conducting boundaries arranged in surfaces of large radii of curvature in combination with an elevated terminal of great surface supported at points of low electric density, substantially as described. NIKOLA TESLA. Witnesses: John C. Kerr, M. Lawson Dyer. |

| METHOD OF AND APPARATUS FOR CONTROLLING MECHANISM OF MOVING VESSELS OR VEHICLES |

|

|